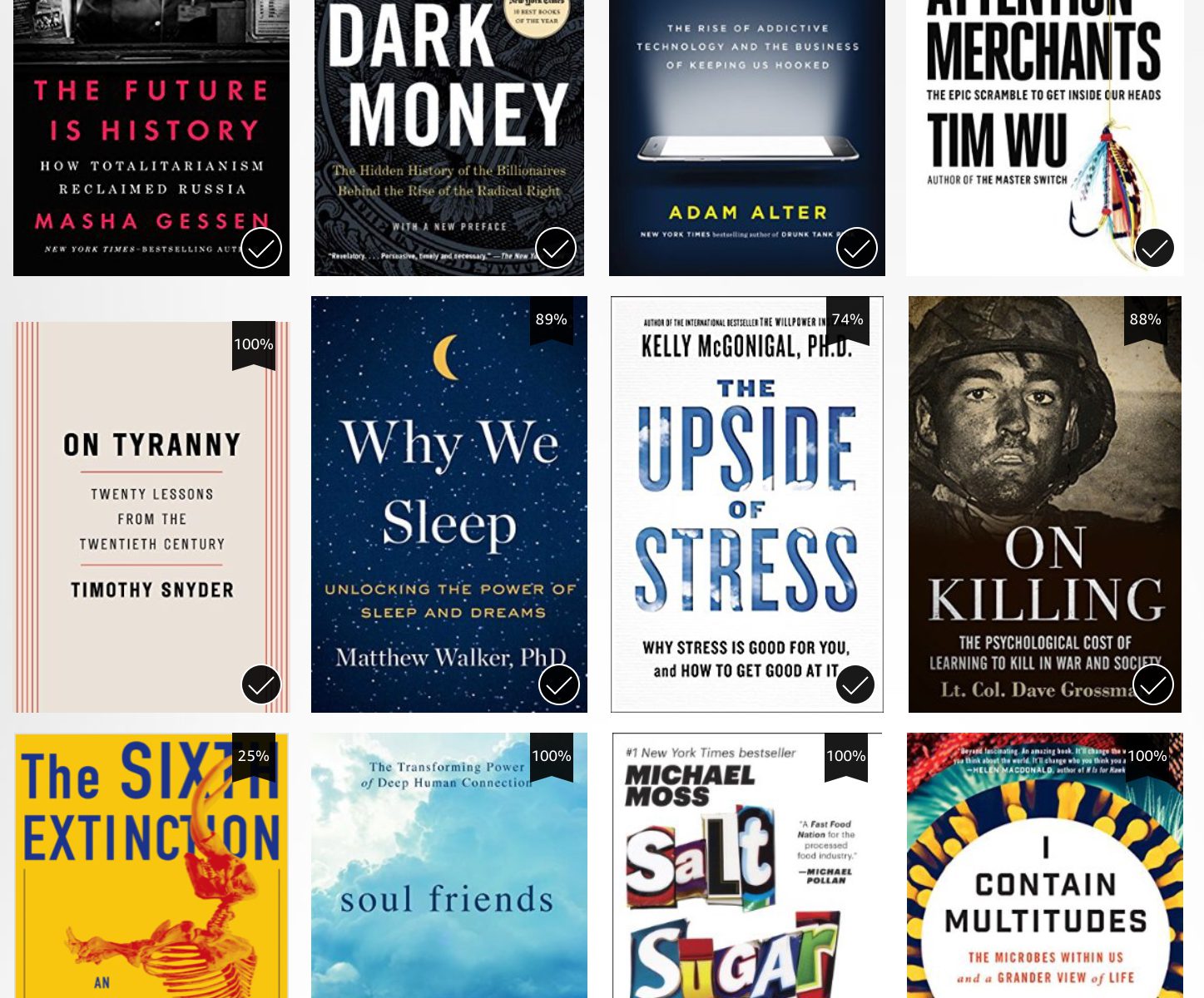

Two things make a book truly important to read. First is urgency. Does it contain information that could immediately protect you from harm or improve your life? That’s pretty important. Second, could this book change the whole way you look at the world, and maybe even revolutionize the way you live? These books have that potential. Check them out:

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams (2017) by Matthew Walker (ebook & print). This is easily the most important book I read in 2017. Why? Because there is nothing more important in your life than sleep. And Westerners (especially Americans) are chronically sleep-deprived, leading to unnecessary car crashes, illness, and depression. We also have terrible sleep hygiene. I’ve been researching this topic for my own book, so I know this is the only decent, up-to-date book out there on sleep. And it’s fantastic. Walker is a renowned sleep researcher himself at UC Berkeley, featuring some of his original findings in the book. All adults interested in their own health should read this. 9.5/10

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (2017) by Timothy Snyder (ebook & print). “Americans today are no wiser than the Europeans who saw democracy yield to fascism, Nazism, or communism in the twentieth century. Our one advantage is that we might learn from their experience. Now is a good time to do so.” Tyranny is on the march not only in the US, but all over the world. Snyder reminds us that we’ve seen this movie before, and it does not end well — unless we get off our asses and do something about it. Let this book be your wake-up call. Prescient, cautionary, essential reading for our times. At 128 pages and less than $7, you cannot afford not to read this. 9.5/10

The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads (2016) by Tim Wu (ebook & print). Our lives are what we pay attention to, so “how we spend the brutally limited resource of our attention will determine those lives to a degree most of us may prefer not to think about.” Prof Tim Wu of Columbia (of Net Neutrality fame) takes us on a ride from the beginning of the attention economy to the age of social media. Benjamin Day, founder of the New York Sun, was the first to sell his paper at a loss to make it up in advertising revenue, figuring out that his readers were not his consumers but his product. The whole advertising and marketing industries originated in patent medicine and propaganda. Heck, all advertising used to be called propaganda. Wu covers a lot of fascinating ground here: the rise of radio and TV networks; war propaganda; Marshall McLuhan, Timothy Leary and LSD; video games and Facebook. This is a thorough history and cautionary tale about the hijacking of our attention by insidious commercial and governmental forces: “Technologies designed to increase our control over our attention will sometimes have the very opposite effect. They open us up to a stream of instinctive selections, and tiny rewards, the sum of which may be no reward at all.” 9/10

Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked (2017) by Adam Alter (ebook & print). While Wu gives you the sweep of history, Alter tells you what’s happening to you right now. Behavioral addiction is affecting millions, making Irresistible one of the most important books I read in 2017. So how do people get hooked? “Behavioral addiction consists of six ingredients: compelling goals that are just beyond reach; irresistible and unpredictable positive feedback; a sense of incremental progress and improvement; tasks that become slowly more difficult over time; unresolved tensions that demand resolution; and strong social connections.” Remember that thousands of extremely smart, highly-compensated people are on the other side of your screen, thinking of ways of keeping you hooked. This book tells you how they do it. 9.5/10

Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right (2016), by Jane Mayer (ebook & print). I’ve read a lot of depressing books in my day, like Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee or King Leopold’s Ghost, or the one right above about how everything is going to die. But somehow those tales of mass slaughter were not nearly as big a downer as Dark Money. David and Charles Koch are the billionaires at the center of the concerted effort to purchase American democracy to do the bidding of the ultra-rich. Them and other characters who consistently lack decency, like Richard Mellon Scaife and the DeVos family create front companies and multilayered shell entities to pass the Citizens United verdict, and create the Tea Party, and fund it to the tune of hundreds of millions. The detailed account of their successful experiment in South Carolina is particularly chilling. Not fun to read, but fascinating nonetheless, and utterly crucial. 9/10

The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (2017), by Masha Gessen (ebook & print). I just knew this book had to be dangerously good when I saw all the 1-star reviews by trolls on Amazon. So I bought it immediately. I had read several of Gessen’s meticulous and eye-opening New Yorker pieces, but this book takes it to a whole new level. And happy to report that it has since won the National Book Award, haters be damned.

Gessen tells the story through seven dramatis personae, each “both ‘regular’, in that their experiences exemplified the experiences of millions of others, and extraordinary: intelligent, passionate, introspective, able to tell their stories vividly.” They give first-person accounts of the everyday ordeal of surviving true to oneself in Russia. Like Zhanna, daughter of popular opposition politician Boris Nemtsov and activist in her own right, whose life demonstrates some of the consequences of opposing the regime (e.g. exile, incarceration and murder — y’know, the yoozh). The story of Masha the journalist illustrates the perils of truthtelling. Pioneering psychotherapist Marina Arutyunyan tries to shepherd modern mental health to Russia through lacerating thickets of state-mandated ideology. Openly gay academic Lyosha tries to advocate for oppressed minorities without getting fired from his precarious university post.

Gessen weaves the last century of Russian history through the lives of the protagonists. Stalin’s self-cannibalizing reign of terror is particularly chilling: “Stalin’s terror machine executed its executioners at regular intervals. In 1938 alone, forty-two thousand investigators who had taken part in the great industrial-scale purges were executed, as was the chief of the secret police, Nikolai Yezhov.” Stalin once invited an old friend from Georgia to Moscow for a reunion, and after lavishly wining and dining him, had him executed before dawn: “This could not be explained with any words or ideas available to man.”

And that is the most astonishing aspect of this book: it is not fiction. The protagonists’ experiences are so logic-defying, so disheartening, and such violations of basic human decency as to exist in a separate universe that no novelist could concoct. And yet, this universe has an internal logic. Perhaps it’s best explained through Hannah Arendt, whose three-volume “Origins of Totalitarianism” Gessen deftly scrunches down to a few essential paragraphs: “What distinguishes a totalitarian ideology is its utterly insular quality. It purports to explain the entire world and everything in it. There is no gap between totalitarian ideology and reality because totalitarian ideology contains all of reality within itself.”

And yet, the book reads like a novel, which is why I don’t want to give away too much. Who is Homo sovieticus? For whom do Russians vote in the “Greatest Russian Ever” (aka “Name of Russia”) contest year after year? What’s going to happen to Boris Nemtsov after he defies Putin? Do our heroes avoid getting beat up and arrested at the demonstrations? Why is Putin so popular in Russia?

One pervasive theme of the book is the hegemony of doublethink over the Russian psyche. Coined by Orwell in “1984”, doublethink is the necessity of maintaining two contradictory beliefs for survival, e.g. publicly supporting the government ideology while knowing that it oppresses your very existence.

This is some crazy-making stuff that Russians seem to have been put through for over a century. And yet, there are still people who fight for truth, healing, and freedom. Over and over, they rise to attend banned protests very likely to land them in jail (or worse). Their stories of stupendous bravery and selflessness consistently inspire.

And lest you as a Westerner think that you’re somehow safe because, oh, this is something happening elsewhere, please note that the recent rise of authoritarianism in countries like America takes its playbook straight out of Russia. Attacks on the press, construction of alternate realities, propagation of fake news, persecution of minorities, and the shameless grabbing of executive power: it’s all happening right now.

And you know what else? We’ve seen it all before: Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, Mao. So don’t read this book just because it’s a riveting account of life in what’s still an undiscovered continent for most Westerners. Don’t read it just because it’s a tour de force of journalistic craft and bravery. Read it because it also informs your life as an American, German, Frenchman, Hungarian, or anyone who values the freedom of human life and ideas, and so that you may be impelled to action. 10/10

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World (2011) by Daniel Yergin (ebook, print & audio). Yergin is the pre-eminent scholar on global energy. Intimidated by the sheer bulk of his tomes (the other being The Prize, for which he nabbed another prize called the Pulitzer), I had avoided them till now. But the audiobook was a manageable way to digest this work piecemeal (also, you can’t tell how thick an audiobook is). It’s safe to say no other book has helped me understand global dynamics of energy and politics better than this one.

Yergin is a master storyteller, weaving together a compelling narrative out of the encyclopedic amount of data he covers — Saudi Arabia and ARAMCO, the Kuwait war, Iran, Angola, renewable energy, Russia, China, and scads more. His exposition on the natural history of the petrostate — a country rendered inherently unstable because of its heavily petroleum-dependent income — and the rise and fall of Cesar Chavez in Venezuela was particularly memorable. A contemporary classic. Read it to better understand your world. 10/10

Blind Spot: Hidden Biases of Good People (2013) by Mahzarin Banaji & Anthony Greenwald (ebook & print). How reliable is your own mind? Are you a nice person? Well, it turns out that just the phrasing of a question can dramatically change the way you recall an event. Self-proclaimed non-racists turn out to harbor hidden biases against all kinds of races. And not only are men willing to take a 11% pay cut to have a male boss, but women are, too. Banaji and Greenwald are venerable professors of psychology whose work reveals our hidden biases owing to a lifetime of exposure to cultural attitudes about age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, social class, sexuality, disability status, and nationality. The authors have many tests in the book to reveal our own mind bugs in real time, making this a delightfully disturbing book. You can even take some free Implicit Association Tests online for fun. After reading this, you will know a lot more about how little you know yourself. 9/10

I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life (2016) by Ed Yong (ebook & print). Did you know that your right hand shares just a sixth of its microbial species with your left hand? Why is a third of human milk made of oligosaccharides that babies can’t digest? The microbiome revolution is upon us, which means it’s time to find out more about the tiny organisms that effectively run life on the planet. The degree to which humans and every other life form depend on microbes for their proper functioning is staggering. Microbes can alter our mood, quell autoimmune disease, soothe irritable bowel syndrome, and protect us against noxious invaders.

Yong, a multi-award winning science journalist, guides with a steady hand through the fantastically rich world of microbes, providing an accessible amount of detail spiked with occasional English wit. The science coming out of this field is upending long-held assumptions on a daily basis, 95% of which I never encountered in medical school. For example: “The immune system’s main function is to manage our relationships with our resident microbes. It’s more about balance and good management than defence and destruction.” The oligosaccharides I mentioned earlier are there to feed the gut bacteria that are wholly intertwined with the baby’s health. If you’re in the mood for a tour through an undiscovered universe that undergirds your entire existence and just happens to live inside you, this book’s for you. 9/10

Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (2013) by Michael Moss (ebook & print). Why does Big Food employs thousands of really smart people to figure out stuff like the “bliss point”, the amount of sugar, salt and fat in a food that evokes the maximum amount of pleasure in the eater’s brain? Because that’s how it can make its products addictive, just like heroin or crack. And judging from the ever-expanding American (and world) waistlines, their methods are working spectacularly.

As someone in the health field, I thought I knew about this stuff. Oh no I didn’t. The incredibly devious, deliberate ways the food companies set out to addict everyone, regardless of health consequences, can only be described as evil. Because profits! As a result, Americans are in the midst of a health crisis unprecedented in the history of mankind, namely the obesity and diabetes pandemic. Read this book to arm yourself against the Nestlés, General Mills, and Krafts of the world who have the determination and resources to make you and your family unhealthy. 9/10

Soul Friends: The Transforming Power of Deep Human Connection (2017) Stephen Cope (ebook & print). Cope’s last book, The Great Work of Your Life, is one of my all-time favorites, which I buy in stacks to give away to friends. So I was eager to read his newest creation. The Senior Scholar-in-Residence at the Kripalu Center for over 25 years, Cope turns his learned, wise and compassionate mind towards the topic of deep friendship. He shares stories about friendships and mentorships of his own, as well as historical accounts from the likes of Eleanor Roosevelt, Charles Darwin, and Queen Victoria. In a world that seems to be too busy for authentic connection, Cope reminds us of the urgency and transformative power of deep friendship. So good. 9/10

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (2015) by Elizabeth Kolbert (ebook & print). Caves that recently contained millions of bats now have none — a fungus massacred them. All frogs are vanishing from the face of the earth. “A third of all reef-building corals, a third of all freshwater mollusks, a third of sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles and a sixth of all birds are headed to oblivion.” There have been five major extinctions on Earth, and we seem to be amidst the sixth one, largely created by humans. Kolbert of The New Yorker is the human reporting on this for the past decade with a sharp eye, steady voice, and muddy boot. Her unsentimental delivery makes the magnitude of the catastrophe hit you even harder when it finally dawns on you: yup, we’re killing everything. This won the Pulitzer Prize, and may it win any and every award that will make kids better stewards of their only planet. I give it a 10 because not destroying all life forms on Earth is kinda important. May want to stop eating tuna and shark-fin soup, like, now. 10/10

On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (2014 revised edition), by Lt Col Dave Grossman (ebook & print). My friend who’s a prison educator and eloquent speaker on violence and restorative justice turned me on to this book. Since its initial publication in 1995, this book has become required reading at the FBI Academy, DEA Academy, West Point, US Marine Corps, and US Air Force — and for good reason. Main thesis: killing comes unnaturally even to soldiers whose own lives are at stake, as evidenced by the low shooting rates (15-20%) in the Civil War, WW I and WW II. This changed with Vietnam, where extensive training in reflexive shooting and desensitization got the rates up to 95%. What did not change, however, was the traumatic effects the killings had on the soldiers committing them. Grossman — Army Ranger and psychology professor, amongst many other credentials — is about as omnicompetent and thoughtful as humans come. He places much of the blame for our cultural desensitization to killing on violent entertainment. The depictions of battle experiences can be gut-wrenching, and yet the glimmers of nobility amongst the obedient carnage is cause for hope. Required reading for understanding modern civilization and the warfare that supports it.

The Power of Persuasion: How We’re Bought and Sold (2005) by Robert A. Levine, Ph.D. (ebook & print) “The psychology of persuasion emanates from three directions: the characteristics of the source, the mind-set of the target person, and the psychological context within which the communication takes place.” Thus begins this revelatory and sobering treatise on the ways humans fool themselves and others. A professor and practicing psychologist for 40+ years, Levine signed up to experience firsthand the persuasive techniques of people like car dealers, door-to-door salesmen (Cutco knives), and cult leaders (the Moonies). One of his key insights is that no one is impervious; we are all susceptible. The persuasiveness triad: “perceived authority, honesty, and likability.” Americans are particularly susceptible to the authority symbols of titles, clothing, and luxury cars (see: current US president). Decisive, swift talkers are no more sure of their facts than more hesitant counterparts, but they create an impression of confidence that audiences perceive as more expert and intelligent. The more jargon you use and the less a jury understands a witness, the more convincing she appears.

Aside from the dismaying news that we’re all patsies waiting to be taken, the book is full of entertaining, insightful stories on scoundrels ranging from psychics to gurus. Moonies recruit in a trademark sequence of “pickup, first date, love bomb”, creeping up on victims with imperceptible subtlety that ultimately engulfs them. Levine’s account of the 10-step method of car salesmen was particularly revelatory and unsettling in the frankness of its manipulation.

The most gripping part of the book was Levine’s depiction of the final hours of the Jonestown cult of Jim Jones, during which 900 members committed suicide by drinking cyanide-laced Kool-Aid, even after witnessing their own infants’ agonizing death throes. To read the transcript of the recording of those hours, and how people just like you and me were rooting for their own demise out of loyalty to a demented and manipulative leader, is to understand how tyranny works, and how it is happening right here, right now. 8.5/10

The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It (2015) by Jane McGonigal (ebook and print). “The latest science reveals that stress can make you smarter, stronger, and more successful. It helps you learn and grow. It can even inspire courage and compassion.” A popular lecturer in psychology at Stanford, McGonigal provides ample evidence to support the radical thesis that stress can be good for you, provided that you think of it as friend rather than foe. You can do this by reframing “anxiety” about an upcoming performance as its physiologically identical counterpart known as “excitement.” Or by re-thinking threats as challenges. Or by watching a video about “how stress can increase physical resilience, enhance focus, deepen relationships, and strengthen personal values.” Or by just telling someone “You’re the kind of person whose performance improves under pressure”, which increases their actual performance by 33%. Or taking 10 minutes to write down your core values.

Some of these one-time interventions continue to work for months and even years. “The things that protect us from the dreaded dangers of stress are all attainable”; McGonigal eloquently conveys the science and practical steps to attain them. This is a life-changing book that can positively affect your health, success and relationships for years. 8.5/10

The Blue Zones: 9 Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest (2012), by Dan Buettner (ebook & print). Dan Buettner’s fantastic 2012 New York Times Magazine Article, “The Island Where People Forgot to Die”, was my introduction to Blue Zones. Are there places in the world where people disproportionately live to be 100 or more? And if so, what’s their secret?

With the backing of National Geographic, Buettner and his crack team of top-notch scientists went around the world and found 5 places that fit the strict Blue Zones criteria: Sardinia, Italy; Okinawa, Japan; Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica; the Seventh-Day Adventist community of Loma Linda, California; and the Greek island of Ikaria. These regions have a disproportionately high population of centenarians, up to 50 times the US average. But even more remarkable, their centenarians are independent at a rate far higher than in the US and Europe: 90% vs 15%. What’s going on?

Having gone to medical school and read the NYT Magazine article, I thought I knew what was in the book and thus postponed reading it. That was a mistake. Buettner and team are incredibly thorough in their approach, uncovering details about living a good life that casual observation would miss. And they back every one of their conclusions with as much data as they can.

Definite patterns emerge amongst the various groups. All of them foster a strong sense of community and intergenerational cohesiveness. In Costa Rica, there’s a 99-person village all descended from one person, and there’s a touching picture of a blissed-out 104-year old lady holding her great-great-granddaughter. People hang out with family and friends every day, and the elderly live with their offspring.

All the communities eat a mostly plant-based diet. Exercise is also built into their daily activity. Although it’s safe to say that none of these people have ever stepped into a gym, every day they till fields, work gardens, tend sheep over hilly terrain, and walk around.

Some other data points also emerge. Several of the communities incorporate goat milk products in their diet, which is more nutritious than cow’s milk. Red wine features prominently in the two Mediterranean communities, with Sardinian Cannonau offering an extra dose of antioxidants. Almost all the communities eat diets rich in beans.

Although I hope you find this review useful, there are several reasons to read the book in its entirety. First, there are a lot of practices worth incorporating into your own life that I don’t have room to mention in detail, e.g. “ikigai”, your reason to get up in the morning; “moai”, a group of friends who meet regularly; and turmeric.

Second, by reading the stories of all five communities, you not only get the details but also the gestalt of living a long and fruitful life. Is there a worldview that predisposes to healthy longevity?

Third, the healthy, functioning centenarians profiled will turn your preconceptions of aging upside down. They also have sterling advice to offer: “Eat your vegetables, have a positive outlook, be kind to people, and smile.”

Fourth and most important: do you really have something better to do than learning how to live a long, productive and healthy life? If so, I’d like to know what that is. In the meantime, I also got the book for my parents, and would encourage you to do the same. Its life-affirming message is invigorating and wise for all future centenarians. 10/10

The Blue Zones of Happiness: Lessons from the World’s Happiest People (2017) by Dan Buettner (ebook & print). A National Geographic cover story hooked me into this book, and happiness is my beat anyway, so there really was no avoiding this one. The central idea: if you set up a framework for a more satisfying life, you’re more likely to have one.

Pleasure, purpose, pride: these are the three intertwining strands constituting the robust rope of happiness. The Danes, perennially at the top of world happiness surveys, have a lot of their basic needs met by their generous government services. Danes also have a strong community ethos, so they join lots of clubs and engage in purposeful activities. Costa Ricans, who may have an even stronger community ethos, have lives full of pleasurable moments or “positive affect”: walking to work, joking with friends, playing with their kids. Singaporeans work 60hr weeks to get the 5 C’s: car, condominium, cash, credit card, and club membership. They take pride in their accomplishments, and that supposedly makes them happy. I have not been to Singapore, but the description of their harried, materialistic lives seemed the antipodes of happiness.

What I really appreciate about Buettner’s work is his thoroughness. He goes into the field with a bunch of scientists, gathers the data, crunches the numbers, and presents us with the best practices. That’s why this book led me to his first Blue Zones book, on longevity, which I consider definitive (also reviewed here). He’s also clear-eyed on the benefits of positive psychology: “They may work in the short run, but they almost always fail over time. They’re quick fixes that may evaporate before you know it.” To be happy in the long run, structure a happy life.

I read this book in a day and highlighted 240 passages. It’s fantastic, and should be required reading for all bipeds. As a bonus, the appendix has a collection of Top 10 happiness practices from leading experts for both individuals and countries, if you just happen to lead one. 9.5/10

The Psychopath Whisperer: The Science of Those Without Conscience (2014) by Kent Kiehl, Ph.D. (ebook & print). Kiehl is one of the few scientists in the world to take a mobile MRI unit into maximum-security prisons to scan the brains of dozens of remorseless criminals. Whereas the average North American male’s score on the Hare Psychopathy Checklist is 4, these serial rapists and murderers score 30 or above. “Lack of empathy, guilt or remorse; glibness; superficiality; parasitic orientation; flat affect; irresponsibility; and impulsivity” characterize psychopaths.

There are some fascinating facts here. The triad of bed-wetting, fire-setting and animal cruelty “predict a child who is on a trajectory toward future severe antisocial behavior as a teenager and adult.” Psychopaths cannot grasp abstract concepts, rarely know details about their children, are hard to startle, and do not get distressed by being in prison. Case histories of inmates like “Gordon” with his attempted long-con on a still-green Kiehl, and the utterly vicious “Shock Richie”, are sobering and instructive. Presidential assassin Charles Guiteau was a psychopath while John Wilkes Booth was not, making for an interesting historical comparison.

About half the book is a mildly self-congratulatory memoir of Kiehl’s illustrious scientific career; less of that may have made for a stronger book. Otherwise, this is very useful stuff. Read this to sharpen your detectors for the 1 in 150 people who fit the psychopath profile so you can protect yourself from them. 8/10

Windfall: How the New Energy Abundance Upends Global Politics and Strengthens America’s Power by Meghan L O’Sullivan (ebook, print, & audio). Main premise: the rise of unconventional energy sources in the US — shale gas and oil plus renewables — will reduce American dependency on foreign energy, tipping the balance of power away from the Middle East, Russia and China and back towards the US. As one would expect from a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, O’Sullivan’s research is meticulous in supporting her thesis. It’s an up-to-date account of the flow of global energy and its concomitant distortions of the fields of power and diplomacy, and a good complement to Daniel Yergin’s definitive The Quest (also reviewed here). O’Sullivan served as an advisor in Iraq under Bush II, so a lot of her observations on petropolitics are firsthand. Her political leanings may also account for her treatment of unconventional gas and oil (read: fracking and tar sands) as unalloyed boons, sidestepping their well-documented environmental hazards and unsustainability. 8.5/10

Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World (2015) by Matthieu Ricard (ebook, print and audio). I picked up “Altruism” at Matthieu Ricard’s reading in San Francisco two years ago. Ricard is a remarkable man: Tibetan Buddhist monk with over 30,000 hours of meditation under his belt; French translator to the Dalai Lama; PhD from Institut Pasteur under Nobelist François Jacob; and current title-holder for “world’s happiest man”, according to brain scans done at Richard Davidson’s lab.

This kind of book is required reading in my line of work, especially when written with the rigor and depth that Ricard brings. At 43 chapters and 849 pages, it’s has the heft of a brick, and the density, too, with tangled sentences like this: “It now had to be demonstrated that people don’t act solely in order to avoid having to justify their non-intervention to themselves either.”

A magnum opus like this takes 5-10x longer to read than the average book. But the rewards can be immense. Ricard brings massive evidence arguing for altruism as an essential part of our human and animal makeup, even beyond the genetic arguments of kin selection. This has far-reaching consequences in how we run our lives, interact with others, and treat the planet. 10/10

Blind Spot: Hidden Biases of Good People (2013) by Mahzarin Banaji & Anthony Greenwald (ebook & print). How reliable is your own mind? Are you a nice person? Well, the way I phrase a question can dramatically change the way you recall an event. Self-proclaimed non-racists people turn out to harbor hidden biases against all kinds of races. And not only are men willing to take a 11% pay cut to have a male boss, but women are, too. Banaji and Greenwald are venerable professors of psychology whose work reveals our hidden biases owing to a lifetime of exposure to cultural attitudes about age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, social class, sexuality, disability status, and nationality. The authors have many tests in the book to reveal our own mind bugs in real time, making this a delightfully disturbing book. You can even take some free Implicit Association Tests online for fun. After reading this, you will know a lot more about how little you know yourself. 9/10

Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are (2017) by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz (ebook & print). Big data gives us four new powers: new types of data, access to honest data, allowing us to zoom in on small subsets of people, and the ability to run causal experiments. These powers can reveal peculiar patterns, e.g. when the author finds that the search term with the highest correlation with the unemployment rate is the name of a porn site (“Slutload”, for the eternally, pruriently curious).

Stephens-Davidowitz spins a compulsively readable yarn with scores of findings ranging from the merely counterintuitive to downright shocking, e.g. “if someone says he will pay you back, he won’t pay you back”; men worry a lot about their penis size; or the porn watching habits of women. There are specific linguistic markers that reveal if your date is into you, e.g. using the word “I” a lot (too many questions, on the other hand, are bad). All of this points to the previously squishy discipline of social science becoming more and more of a science — and one that can actually improve our lives. Loved it! 9/10

The Art of Loving (1956) by Erich Fromm (ebook & print). This is a classic by a guy who should be far more widely read in this country. Heck, if I was King of the Universe, I’d make it mandatory reading for every high school kid. This guy drops truth bomb like Kissinger on Cambodia: surreptitiously but in abundance. Here’s one: “It is hardly necessary to stress the fact that the ability to love as an act of giving depends on the character development of the person. It presupposes the attainment of a predominantly productive orientation; in this orientation the person has overcome dependency, narcissistic omnipotence, the wish to exploit others, or to hoard, and has acquired faith in his own human powers, courage to rely on his powers in the attainment of his goals. To the degree that these qualities are lacking, he is afraid of giving himself—hence of loving.” Damn! 80 highlights in 104 pages = most highlights per page of any book I’ve ever read. Insanely prescient; everything he said 50 years ago rings true today. No one should get married before reading and internalizing this first. 10/10

Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (2015) by Benedict Anderson (ebook & print). The writing is abstruse, wordy and jargon-filled, meaning it’s a scholarly book by an academic. The basic premise: the current organization of the world into countries is a wholly fictional recent invention, started in the 19th century by South American expats (“creoles”) from European countries inspired by the example of the United States. That a bunch of heterogeneous Spaniards, mestizos, and natives should suddenly feel “Bolivian” or “Colombian” is more a feat of the imagination than anything pre-ordained or natural. It’s an important book, but one that no one should have to read. 8/10